In Honour of that High and Mighty Princess, Queen Elizabeth

By Anne Bradstreet

Introduction

Anne Bradstreet’s Puritan family immigrated to North America in 1630, exchanging the comforts of England for the rigours of colonial life, where she began writing poetry.[1]

Written around 1643, Bradstreet’s poem about Elizabeth I challenges seventeenth-century patriarchal views of women as ‘the weaker vessel’.[2] Despite Elizabeth’s death over forty years earlier, Bradstreet advances her to near-divine status, portraying her as superior to men in both governance and virtue. The poem presents Elizabeth as a powerful archetype, aligning her with symbolic female figures from mythology, history, and the Bible to construct a layered allegory of female empowerment. Bradstreet invokes the phoenix multiple times, a mythical bird that regenerates every five hundred years by bursting into flame and rising from its ashes.[3] It acts as a symbol of rebirth and chastity, serving as an emblem of Elizabeth’s singularity and legendary status as a monarch.[4] See figure 1.

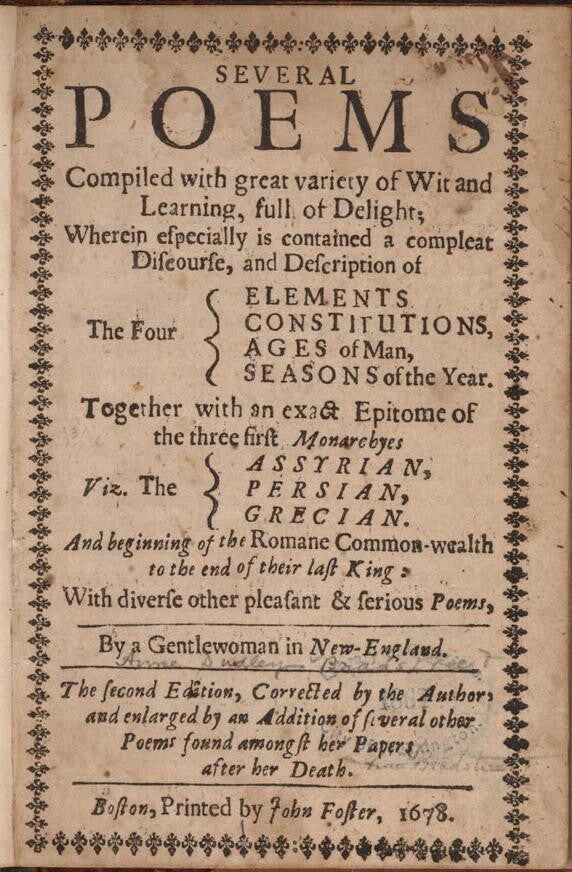

Printed in England in 1650, The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung up in America became the first collection of poetry to be published by a New World author. Bradstreet’s brother-in-law, John Woodbridge, had taken her manuscripts to London, claiming it was without her knowledge. He wrote in the book, ‘I feel the displeasure of no person in the publishing of these poems, but the authors, without whose knowledge […] I have presumed to bring to public view.’[5] Scholars, however, perceive this as a ruse to endorse Bradstreet as a female writer. Her name appears several pages in, where she is acknowledged as the author of the poems. This is preceded by many male accolades serving as a seventeenth-century-style blurb that advocates her work.[6]

Bradstreet was one of the very few women to publish under her own name; two of her contemporaries, Rachel Speght (A Mouzell for Melastomus, 1617) and Margaret Cavendish (Poems and Fancies, 1653) did likewise. [7] This underscores Bradstreet’s achievement, which defied prevailing social norms.

The title of Bradstreet’s book, The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung up in America, affirms her literary ambition by aligning her with the classical nine Muses, goddesses of artistic and intellectual inspiration. This allusion echoes her tribute to Queen Elizabeth, positioning Bradstreet as a worthy voice in a male-dominated poetic tradition.[8] Woodbridge writes in his preamble,

What you have done, the sun shall witnesse beare,

That for a womans Work ‘tis very rare;

And if the Nine vouchsafe the Tenth a place,

I think they rightly may yield you that grace.

This quotation highlights Bradstreet’s literary stature and affirms her depiction of Elizabeth as a monarch revered for her embodiment of female authority and resilience.

Anne Bradstreet – Biography, Read more

[1] Jeannine Hensley, introduction to The Works of Anne Bradstreet (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967), p. ix.

[2] Antonia Fraser, The Weaker Vessel: Women’s Lot on Seventeenth-Century England, Part One (London: Phoenix, 2002), p. 1.

[3] OED, s.v., ‘Phoenix’

[4] National Portrait Gallery,<https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw02074/Queen-Elizabeth-I>[accessed 14 November 2025].

[5] Anne Bradstreet, The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung up in America (London: 1650), p. 12.

[6] Christy L Pottroff, ‘Bradstreet, Anne’, in The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Early Women’s Writing, ed. by Patricia Pender and Rosalind Smith (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2025), 1–6 (p. 3).

[7] See: Rachel Speght, A Mouzell for Melastomus (London, 1616), <https://archive.org/details/bim_early-english-books-1475-1640_a-mouzell-for-melastomus_speght-rachel_1616/mode/2up>; and Margaret Cavendish, Poems and Fancies (London, 1653), <https://archive.org/details/bim_early-english-books-1641-1700_poems-and-fancies-_newcastle-margaret-cave_1653/page/n1/mode/2up>.

[8] Anne Buttimer, ‘Musing on Helicon: Root Metaphors and Geography’, Geografiska Annaler. Series B, Human Geography, 64.2, (1982), 89–96 (p. 89).

Figure 1: Nicholas Hilliard, Queen Elizabeth I, c. 1575, oil on panel, 787 x 610 mm, National Portrait Gallery.

This painting is also known as the ‘Phoenix’ portrait, in reference to the phoenix jewel she wears on her chest. Read more about the painting here.

A brief look at Anne Bradstreet's life

See: Cory MacLauchlin, ‘Anne Bradstreet’, YouTube, 5 years ago, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d68HU0OMTHw> [accessed 23 November 2025].

Listen to the poem...

See: Great Books Academy, ‘Anne Bradstreet’, YouTube, 14 February 2018, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d7rEHruG-Z0> [accessed 23 November 2025].

Editorial Note

The transcription covers the Proem and Poem; Her Epitaph and Another can be viewed at The Poetry Foundation, where this version was taken. Most modern interpretations make slight changes. The original poem from the 1650 first edition, The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung up in America, can be viewed here.

Notes on the poem are concise, but further information can be found in the provided references. See: Anne Bradstreet, In Honour of that High and Mighty Princess, Queen Elizabeth, Poetry Foundation <https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43703/in-honour-of-that-high-and-mighty-princess-queen-elizabeth> [accessed 24 November 2025].

Proem/Poem

Proem

Although great Queen, thou now in silence lie,

Yet thy loud Herald Fame, doth to the sky

Thy wondrous worth proclaim, in every clime,

And so has vow’d, whilst there is world or time.

So great’s thy glory, and thine excellence,

The sound thereof raps every human sense

That men account it no impiety

To say thou wert a fleshly Deity.

Thousands bring off’rings (though out of date)

Thy world of honours to accumulate.

‘Mongst hundred Hecatombs of roaring Verse,

‘Mine bleating stands before thy royal Hearse.

Thou never didst, nor canst thou now disdain,

T’ accept the tribute of a loyal Brain.

Thy clemency did yerst esteem as much

The acclamations of the poor, as rich,

Which makes me deem, my rudeness is no wrong,

Though I resound thy greatness ‘mongst the throng.[1]

The Poem

No Phoenix Pen, nor Spenser’s Poetry,

No Speed’s, nor Camden’s learned History;[2]

Eliza’s works, wars, praise, can e’re compact,

The World’s the Theater where she did act.

No memories, nor volumes can contain,

The nine Olymp’ades[3] of her happy reign,

Who was so good, so just, so learn’d, so wise,

From all the Kings on earth she won the prize.

Nor say I more than truly is her due.

Millions will testify that this is true.

She hath wip’d off th’ aspersion of her Sex,

That women wisdom lack to play the Rex.[4]

Spain’s Monarch[5] sa’s not so, not yet his Host:

She taught them better manners to their cost.

The Salic Law[6] had not in force now been,

If France had ever hop’d for such a Queen.

But can you Doctors now this point dispute,

She’s argument enough to make you mute,

Since first the Sun did run, his ne’er runn’d race,

And earth had twice a year, a new old face;[7]

Since time was time, and man unmanly man,

Come shew me such a Phoenix if you can.

Was ever people better rul’d than hers?

Was ever Land more happy, freed from stirs?

Did ever wealth in England so abound?

Her Victories in foreign Coasts resound?

Ships more invincible than Spain’s, her foe

She rack’t, she sack’d, she sunk his Armadoe.[8]

Her stately Troops advanc’d to Lisbon’s wall,

Don Anthony[9] in’s right for to install.

She frankly help’d Franks’ (brave) distressed King,

The States[10] united now her fame do sing.

She their Protectrix was, they well do know,

Unto our dread Virago[11], what they owe.

Her Nobles sacrific’d their noble blood,

Nor men, nor coin she shap’d, to do them good.

The rude untamed Irish she did quell,

And Tiron[12] bound, before her picture fell.

Had ever Prince such Counsellors as she?

Her self Minerva[13] caus’d them so to be.

Such Soldiers, and such Captains never seen,

As were the subjects of our (Pallas) Queen:

Her Sea-men through all straits the world did round,

Terra incognitæ[14] might know her sound.

Her Drake came laded home with Spanish gold,

Her Essex took Cadiz,[15] their Herculean hold.

But time would fail me, so my wit would too,

To tell of half she did, or she could do.

Semiramis[16] to her is but obscure;

More infamy than fame she did procure.

She plac’d her glory but on Babel’s walls,

World's wonder for a time, but yet it falls.

Fierce Tomris (Cirus’ Heads-man, Sythians’ Queen)

Had put her Harness off, had she but seen

Our Amazon i’ th’ Camp at Tilbury,

(Judging all valour, and all Majesty)

Within that Princess to have residence,

And prostrate yielded to her Excellence.[17]

Dido[18] first Foundress of proud Carthage walls

(Who living consummates her Funerals),

A great Eliza, but compar’d with ours,

How vanisheth her glory, wealth, and powers.

Proud profuse Cleopatra, whose wrong name,

Instead of glory, prov’d her Country’s shame:

Of her what worth in Story’s to be seen,

But that she was a rich Ægyptian Queen.

Zenobia,[19] potent Empress of the East,

And of all these without compare the best

(Whom none but great Aurelius could quell)

Yet for our Queen is no fit parallel:

She was a Phoenix Queen, so shall she be,

Her ashes not reviv’d more Phoenix she.

Her personal perfections, who would tell,

Must dip his Pen i’ th’ Heliconian[20] Well,

Which I may not, my pride doth but aspire

To read what others write and then admire.

Now say, have women worth, or have they none?

Or had they some, but with our Queen is’t gone?

Nay Masculines, you have thus tax’d us long,

But she, though dead, will vindicate our wrong.

Let such as say our sex is void of reason

Know ‘tis a slander now, but once was treason.[21]

But happy England, which had such a Queen,

O happy, happy, had those days still been,

But happiness lies in a higher sphere.

Then wonder not, Eliza moves not here.

Full fraught with honour, riches, and with days,

She set, she set, like Titan in his rays.

No more shall rise or set such glorious Sun,

Until the heaven’s great revolution:

If then new things, their old form must retain,

Eliza shall rule Albian once again.

Notes on the Proem/Poem

[1]This preamble is setting up the context of the following stanza, and celebrates Elizabeth’s fame around the world, and although dead, she has left an eternal impression of greatness. The reference to Elizabeth as a deity to men is one of

Bradstreet’s first feminine message. This significance becomes clearer when set against Puritan beliefs about gender roles in both family and community life, where women were regarded as more susceptible to sin and temptation and were expected to embody traits such as modesty and obedience. See: Meridith Styer, ‘The Pen of Puritan Womanhood: Anne Bradstreet’s Personal Poetry as Catechism on Godly Womanhood’, Rhetoric Review, 36.1 (2017), 15–28 (p.18).

[2] Bradstreet opens her poem by referring to renowned writers and poets, suggesting that even their celebrated talents fall short of adequately honouring the Queen.

[3] Olymp’ades: A unit of time equating to four years.

[4] Women do have the wisdom to rule, as well as men and Elizabeth had proven this.

[5] The failed attempt by Phillip II of Spain’s Armada to attack England. See: Helen Castor, Elizabeth I (London: Penguin Books, 2018), p.81.

[6] The Salic Law: A French law which does not allow women rulers.

[7] Bradstreet uses cosmic imagery to emphasise Elizabeth’s greatness.

[8] Elizabeth’s Navy famously defeated the Spanish Armada under Phillip II in 1588. See: Judith M Richards, Elizabeth I (Oxford: Routledge, 2012), p. 141.

[9] Although Elizabeth’s 1589 expedition to support Don Antonio ultimately failed, Bradstreet frames Elizabeth as a politically ambitious yet compassionate monarch, reinforcing her image as a powerful and benevolent female ruler. See: Gordon K. McBride, ‘Elizabethan Foreign Policy in Microcosm: The Portuguese Pretender, 1580-89’, Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies, 5.3 (1973), 193–210 (p. 196).

[10] Elizabeth supported both the Dutch and the French in their struggles against Spanish aggression.

[11] Bradstreet’s use of the term ‘dread [defiant] Virago’ carries strong feminist connotations. Derived from the Latin vir (man), it denotes a woman with masculine strength, often a warrior figure. Thoughtfully applied to Elizabeth, the term evokes both her political power and biblical resonance, as Virago is also associated to Eve in Genesis 2:23. By invoking this word, Bradstreet affirms Elizabeth’s masculine virtues through scriptural authority, framing her as a woman who embodies strength traditionally reserved for men. See: OED, s.v., ‘Virago’; and Genesis 2:23 (The Holy Bible: Authorised King James Version with Apocrypha).

[12] ‘Tiron’ is a variant of ‘Tyrone’, referring to Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, a central figure in Irish resistance against Elizabethan rule. See: Hiram Morgan, ‘Hugh O’Neill and the Nine Years War in Tudor Ireland’, The Historical Journal, 36.1 (1993), 21–37 (p. 21).

[13] Minerva: Roman goddess of wisdom and war.

[14] Latin: Unknown territory.

[15] Sir Frances Drake brought treasure from Spain, and the Earl of Essex captured Cadiz. Such feats were seen as ‘Herculean’ by Bradstreet, using this classical figure to show their scale and importance.

[16] Semiramis, the legendary Assyrian queen known for her martial prowess, carries a legacy of notoriety. Bradstreet places Elizabeth above her, suggesting that while Semiramis’s fame was tainted, Elizabeth’s was rooted in virtue and moral strength. See: Elizabeth Archibold, ‘Sex and Power in Thebes and Babylon: Oedipus and Semiramis in Classical Text’, The Journal of Medieval Latin, 11 (2001), 27–49 (p. 38).

[17] Bradstreet imagines Tomyris, the fierce Scythian queen, surrendering her armour in awe of Elizabeth at Tilbury. By invoking legendary female warriors and showing them humbled, Bradstreet elevates Elizabeth as the true embodiment of majesty and valour. See: Lloyd Llewllyn-Jones, Persians: The Age of Great Kings (London: Headline Publishing Group, 2022), p. 83.

[18] By founding and ruling Carthage, Dido defied the patriarchal expectations of her time. See: Janet Schmalfeldt, ‘In Search of Dido’, The Journal of Musicology, 18.4 (2001), 584–615 (p. 584).

[19] Zenobia was a bold and powerful queen of the Palmyrene Empire who famously stood up to Rome. See: Mary Bergstein, ‘Palmyra and Palmyra: Look On These Stones, Ye Mighty, And Despair’, Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics 24.2 (2016), 13–38 (p. 18).

[20] To write of Elizabeth’s greatness, one must draw inspiration from the ‘Heliconian Well’. Mount Helicon was sacred to the Greek Muses in Greek Mythology. See: Anne Buttimer, ‘Musing on Helicon: Root Metaphors and Geography’, Geografiska Annaler. Series B, Human Geography, 64.2, (1982), 89–96 (p. 89).

[21] Bradstreet confronts the prevailing misogyny by questioning why women are deemed inferior, despite the example of Queen Elizabeth’s accomplished reign. She presents Elizabeth’s leadership as living proof of women’s intelligence and capability, challenging patriarchal assumptions through historical precedent.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

The Bible: Authorised King James Version with Apocrypha (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997)

Bradstreet, Anne, In Honour of that High and Mighty Princess, Queen Elizabeth, Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43703/in-honour-of-that-high-and-mighty-princess-queen-elizabeth [accessed 24 November 2025].

Bradstreet, Anne, The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung up in America (London: 1650)

Cavendish, Margaret, Poems and Fancies (London: 1653)

Hilliard, Nicholas, Queen Elizabeth I, c. 1575, oil on panel, 787 x 610 mm, National Portrait Gallery.

Speght, Rachel, A Mouzell for Melastomus (London: 1616)

Secondary Sources

Archibold, Elizabeth, ‘Sex and Power in Thebes and Babylon: Oedipus and Semiramis in Classical Text’, The Journal of Medieval Latin, 11 (2001), 27–49.

Bergstein, Mary, ‘Palmyra and Palmyra: Look On These Stones, Ye Mighty, And Despair’, Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics, 24.2 (2016), 13–38.

Buttimer, Anne, ‘Musing on Helicon: Root Metaphors and Geography’, Geografiska Annaler. Series B, Human Geography, 64.2 (1982), 89–96.

Castor, Helen, Elizabeth I (London: Penguin Books, 2018)

Fraser, Antonia, The Weaker Vessel: Women’s Lot on Seventeenth-Century England, Part One (London: Phoenix, 2002)

Great Books Academy, ‘Anne Bradstreet’, YouTube, 14 February 2018, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d7rEHruG-Z0> [accessed 23 November 2025].

Hensley, Jeannine, introduction to The Works of Anne Bradstreet (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967).

Hilliard, Nicholas, Queen Elizabeth I, National Portrait Gallery, <https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw02074/Queen-Elizabeth-I> [accessed 14 November 2025].

Llewllyn-Jones, Lloyd, Persians: The Age of Great Kings (London: Headline Publishing Group, 2022)

MacLauchlin, Cory, ‘Anne Bradstreet’, YouTube, 5 years ago, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d68HU0OMTHw> [accessed 23 November 2025].

McBride, Gordon K, ‘Elizabethan Foreign Policy in Microcosm: The Portuguese Pretender, 1580-89’, Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies, 5.3 (1973), 193–210.

Morgan, Hiram, ‘Hugh O’Neill and the Nine Years War in Tudor Ireland’, The Historical Journal, 36.1 (1993), 21–37.

Oxford English Dictionary Online, (Oxford: Oxford University Press) <https://www.oed.com> [accessed 14 November 2025]

Pottroff, Christy L., ‘Bradstreet, Anne’, in The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Early Women’s Writing, ed. by Patricia Pender and Rosalind Smith (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2025), pp. 1–6.

Richards, Judith M, Elizabeth I (Oxford: Routledge, 2012)

Schmalfeldt, Janet, ‘In Search of Dido’, The Journal of Musicology, 18.4 (2001), 584–615.

Styer, Meridith, ‘The Pen of Puritan Womanhood: Anne Bradstreet’s Personal Poetry as Catechism on Godly Womanhood’, Rhetoric Review, 36.1 (2017), 15–28.

Create Your Own Website With Webador